News & Events | About PKU News | Contact | Site Search

Peking University, June 4, 2011: The 54th International Art Exhibition at La Biennale di Venezia opens June 4 at the Arsenale and Giardini. Peng Feng, associate professor with the PKU Department of Philosophy and curator of the China Pavilion, will lead five Chinese artists — Cai Zhisong, Liang Yuanwei, Pan Gongkai, Yang Maoyuan, and Yuan Gong — to participate in the art carnival.

In order to help visitors understand the core theme of the pavilion, Beijing Today interviewed Professor Peng on the eve of his departure to learn more about this upcoming exhibition.

Prof. Peng Feng (File photo)

Yang Maoyuan's All Things are Visible/Photos provided by Prof. Peng Feng

Visitors looking for the former armory, the site of the China Pavilion at the biennale, need only keep an eye out for the huge “artificial clouds” created by artist Cai Zhisong. His white-painted tumbler-like devices are made of steel and house wind chimes and tea.

When rocked by the wind, the clouds emit the scent of tea and the sound of the wind chimes to create what Cai describes as a “dreamy, Zen-Buddhist atmosphere.”

The exotic display is one of five based on traditional elements thought to best represent Chinese culture: tea, lotus, liquor, incense and herbal medicine.

Liang Yuanwei’s work, I Plead: Rain, is a liquid-cycle device that drops huangjiu, a low-proof yellow drink made from fermented grain, into a sink in an endless loop.

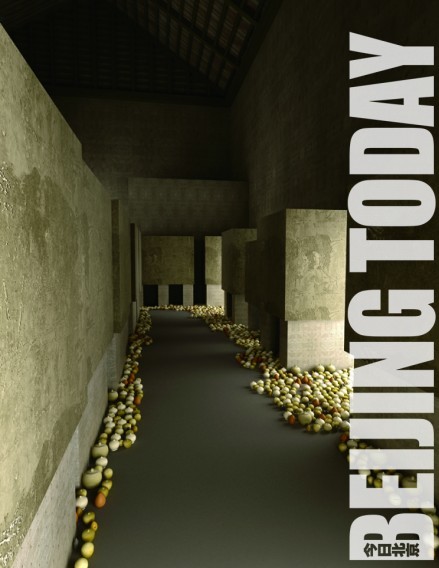

Pan Gongkai’s Rong (Melting) is a 20-meter-long low-temperature corridor filled with lotuses, a symbol of austerity in Chinese culture. On the walls are Pan’s ink-paintings of lotuses, onto which are projected images from On the Border of Western Modern Art, symbolizing cultural coexistence.

Liang Yuanwei's I Plead: Rain

All Things are Visible, Yang Maoyuan’s contribution, is a host of porcelain pots filled with herbal medicines like fengyoujing and huoxiang zhengqi shui, common remedies for summertime ailments.

Yuan Gong’s Empty Incense is a device which combines incense and electronics. The scent is dispersed from nine sources to permeate the pavilion. Light fog is shown on an MP4 player and iPad. The display is inspired by Zen Buddhist teachings that form is emptiness and emptiness is form.

The displays are all interpretations of this year’s biennale theme, “ILLUMInations.”

Pan Gongkai's Rong (Melting)

“Illumination is a basic concept in Christian culture that is explained as divine enlightenment. In Chinese culture, illumination is more explained by sights and smells that help people accumulate and disperse qi (life energy),” said Peng, deputy director of Peking University Aesthetic Research Center.

He said beauty is usually defined by light in Western aesthetics, but Chinese aestheticians find a closer relationship between beauty and taste. “Beauty in Chinese is represented by a big, fat sheep. The illumination of light in Western tradition can be understood in China in the context of flavor,” he said.

Yuan Gong's Empty Incense

The concept of five tastes, sweet, sour, bitter, pungent and salty, is one aspect of the five elements theory — the ancient belief that all things are composed of metal, wood, water, fire and earth. The artists in turn apply this to create exhibits that tantalize the five senses.

“We hope to create an intense experience of emotion that melts through national boundaries. We hope it will bring visitors closer to remote Chinese culture,” he said.

Coming up with this plan for the China Pavilion and dealing with the venue’s restrictions was a brain-racking challenge for Peng.

The dark and damp Arsenale, where the pavilion is located, houses huge oil tanks that reek of diesel and eat up all the space. It was hard to imagine a visual work that would not be tainted by the scent of industrialization, he said.

That’s when he touched on overpowering the area’s scent.

The idea came to him when he used Chinese herbs to help one of his students understand American contemporary art critic Arthur Danto’s post-history interpretation of art.

Cai Zhisong's Cloud-Tea

“Danto says that old works can be regrouped into new categories of contemporary art, which is similar to Chinese medical theory. The herbs used to cure certain ailments never change, but they can be combined with other herbs to cure more conditions.”

He gradually came to associate the smells of liquor, tea and medicine as embodying the Chinese spirit.

“It is obviously silly to use a bigger or more powerful thing to compete with the smell of the oil tanks. Chinese philosophy doesn’t advocate overpowering something with a greater force, but wearing away at it as water breaking through a rock,” he said.

Peng said he also tried to explore two major issues through the exhibition: the relationship between concept and feeling and between traditional and contemporary art.

“The exhibitions at the China Pavilion are concept art, as they convey not only the concept of smell but real smells. They are abstract ways to activate visitors’ sensory organs to appreciate and understand Chinese philosophy,” he said.

Peng said he does not like to distinguish between traditional and contemporary art. He said he prefers to use the exhibitions to explore modern use of traditional elements.

Virgin Garden

“The traditional elements we used are still alive in China, so I hope to challenge the stereotype that traditional art has to be totally split from contemporary art,” he said. “In the age of globalization, artistic expression should demonstrate the intellectual level of modern people instead of being tied up with such a trivial argument.”

Peng said the works were also anti-business, as they could not be collected or sold: when the smell fades, their life ends.

Chinese contemporary art has experienced three stages in the last three decades: in the 1980s, artists engaged in blind imitation of the West. In the 1990s, many Chinese artists went to the US to study Western art and rediscover the value of Chinese art in multicultural North America. But even these artists’ works were made primarily for foreign consumers.

“It was after the economic crisis that Chinese artists began to act on their own and explore more of their own cultural roots,” he said.

Peng said he expects this year’s unique exhibition to go down in biennale history.

This year’s China Pavilion will give Chinese culture a modern footing and seek to create extensive, honest connections with other nations, he said.

Reported by: Li Zhixin

Edited by: Jacques

Source: Beijing Today