News & Events | About PKU News | Contact | Site Search

A special edition of Peking University News in commemorating the 115th anniversary of the university (PKU/Beida).

Peking University, May 4, 2013: “China has been my home for the greater part of my life. I am bound to that great country and people by ineluctable ties of the spirit, not only because of my birth there, but also because of long residence and countless friendships.”

John Leighton Stuart (Situ Leideng), an American missionary educator and diplomat, recalled his China link at the culmination of the early Cold War period.

“It was my privilege to grow up as an American boy in China, to return there later as a missionary and student of Chinese culture,” Stuart wrote in his 1952 memoir Fifty Years in China.

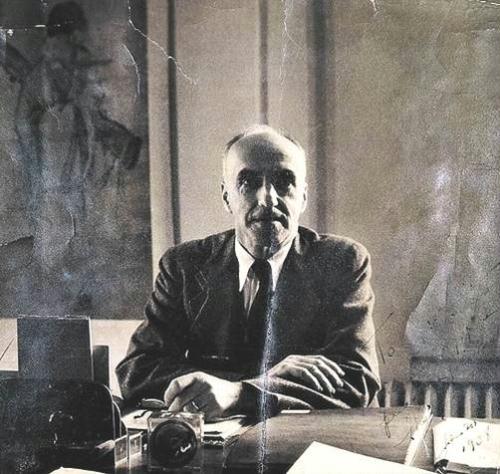

John Leighton Stuart (File photo)

Widely known as the inaugural president of Yenching University, Stuart was later appointed US ambassador to China. Due to the fluctuation of Sino-American relations during his life time, people from both countries passed mixed notices on this intercultural communicator. But the contributions he made to China’s higher education system are widely acknowledged and still notable after half a century of his decease.

Stuart’s family possesses a profound religious background. His father, John Linton Stuart, was one of the first three Presbyterian ministers sent to China by the US Southern Presbyterian Church. And his mother, Mary Louisa Horton, was the founder of the second girls’ school in China, which later became a part of Christian Union Girls’ School of Hangchow (Hangzhou).

Born in China on June 24, 1876, Stuart spent his childhood at Hangzhou City and returned to the US for further study. After graduated from Hampden-Sydney College and Union Theological Seminary, he decided “to put my religious belief to what was for me then the ultimate test.”

He came back to China in 1904, six years after the Reform Movement of 1898 and eight years before the founding of the Chinese Republic, when the country started to undergo dramatic changes. As a missionary educator, Stuart has lived and worked in the country for 50 years.

Stuart firstly preached at Hangzhou for nearly four years and got a teaching position at Nanking Theological Seminary. More than 10 years’ working at Nanjing prepared him to be a seasoned educator and administrator. Then he was invited to Beijing to organize a group of “little missionary colleges” — the Huei Wen University, the North China Union College, and later the North China Union Women's College into a bigger union university.

This union was later named Yanjing Daxue (Yenching University). Stuart was called to Beijing to be the new university's president in 1919, when it was already the eve of China's new round of intellectual renaissance and nationalistic revolution.

Starting almost from nothing, Stuart had to raise fund worldwide in order to build the campus. Meanwhile, he received the estate of Charles M. Hall, an American executive of Alcoa Aluminum and bought the Qing-dynasty royal gardens in Beijing’s northwest suburb, now Yan Yuan. With the help of Henry Luce, his vice president and a resourceful fundraiser, Stuart developed this small missionary institution into a leading university in China.

Map of the new Yenching site: Yan Yuan (1921)

In 1926, Yenching’s new campus at Yan Yuan, “the most beautiful campus in the world” spoken of by “so many visitors in years,” was completed. According to Stuart, a scenic environment would not only improve the aesthetic level of the university but also “help to deepen the attachment of the students to the institution and its international ideals.” After seven years’ elaboration, he finally agreed that “in one respect at least the reality became fairer than my dreams.”

But his dreams never ceased on here. As an educational missionary and president of Yenching, Stuart embraced a grand plan for the development of university education: “In attempting to create the university of my dreams my task seemed to assume a four-fold aspect: its Christian purpose; its academic standards and vocational courses; its relation to the Chinese environment and contribution to international understanding and good will; its financial resources and physical equipment.”

Yenching University was founded by Western Christian leaders to furnish the best quality of intellectual and religious leadership for China. Julean Arnold, who served as American Commercial Attaché during 1914-1940, once said: “The leaders of the new China must be men and women of strong Christian character, if China is to be a blessing to modern civilization.”

The Western world lies great hope upon Yenching University in the training a new group of Chinese youth who have the education to produce a better political and social order in China and who can lead their people to share in a similar task for the world.

John Mott, leader of Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA) and World Student Christian Federation (WSCF), winner of the 1946 Nobel Peace Prize, pointed out the leading position of Yenching University, “I have no hesitation whatever in saying that there should be at Peking one of the strongest Christian Universities, not only in China, but in Asia.”

The university mainly consisted of Theology, Law, Medical, as well as Arts and Science Studies departments, complemented by a college for female students. In 1928, American journalist, educator Walter Williams established a new department of journalism at Yenching. By 1929, the university had developed into three schools and 18 departments. One of the top universities in China, Yenching distinguished itself by a considerable academic freedom.

Stuart recruited major Chinese and Western scholars to teach. In the 1920s, the faculty contained more than 70 members holding degrees from world-class universities such as Yale, Harvard, Princeton, Columbia, Oxford, Cambridge, Edinburgh, Michigan, Cornell, Northwestern, California, Wooster, Missouri, Oberlin, Smith, Holyoke, Goucher, and Wellesley.

Charles Crane, US Minister to China from 1920 to 1921, summed up Yenching’s advantages:

Situated at the political and intellectual capital of the country, Peking University (Yenching University) has unrivalled opportunities to train the national leaders of the future and to raise moral and educational standards throughout the whole country. The attractive grounds recently secured near Peking, the fine quality of the teaching personnel, and the valuable traditions of the older schools are noteworthy assets for the new union enterprise.

Although founded as a Christian college, Yenching respected the freedom of belief among students and faculties. “No required chapel attendance nor compulsory religious services, no academic benefits from profession of Christian faith nor corresponding handicaps from refusal.” Stuart tended to establish “a real university”, where “truth was taught untrammeled” and “faith or its outward expression was treated as a personal matter.”

During his 27 years in office, Stuart demonstrated the idea of liberal and comprehensive education, “My job was to leave the teachers as nearly free as possible for their own duties. None the less there was a zest for me in all the details of our program.”

Yenching trained a generation of talents in sciences and culture. The total enrollment of the university was less than 1,000 among which there were 53 who later became members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) and of the Chinese Academy of Engineering (CAE), and during the Second World War, nine tenths of overseas Chinese corresponds were Yenching alumni.

In 1928 the Harvard-Yenching Institute, dedicated to the education of humanity and social sciences in East Asia and Southeast Asia, was established by Yenching University and Harvard University. It still exists on the Harvard campus in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

“Among many other advantages to Yenching,” Stuart once noted, “the Harvard-Yenching Institute of Chinese Studies has enabled us and through us several other Christian colleges in China to develop Chinese studies fully up to the best standards of any purely Chinese institution.”

Stuart also spoke highly of Chinese student, “remembering their historical background and the disordered conditions of contemporary national life, they have on the whole made their way against many obstacles and manifested a character and spirit which is far beyond what I would have prophesied.” In the youth of China, he saw the “ample evidence of what fine material is,” “vitality and mental capacity of the race,” and “effectiveness of education conceived as the self-expression of the whole personality.”

Stuart guided the university through the Japanese occupation. In 1937, Japanese troops overran Beijing, then named Beiping. When facing Japanese military commands that to fly the puppet regime flag on Yenching campus and express thankfulness for Japan's so-called liberation, Stuart provided a resolute declination, “We are refusing to comply with these orders.”

After being imprisoned from 1941 to 1945, Stuart was released and supervised reconstruction until General Marshall, Chief of Staff of the Army, came to China. And within two month’s acquaintance, Stuart impressed this military leader so much that in July 1946, Marshall appointed him ambassador to China as the general wrote:

I found his advice and leading assistance of invaluable help to me. I doubt if there is anyone whose understanding of Chinese character, history, and political complications equals that of Dr. Stuart. … It is the man, the man, the character and the general range of his experience which appealed to me.

In August 1949, Stuart left China, coinciding with the US government’s publication of The China White Paper. After the 1952 nationwide restructuring of colleges and departments, Yenching University was merged with other universities. But Stuart always kept faith to the “spiritual energies” of Yenching both in “its institutional witness and through the lives of its students.”

When witnessing the further deterioration of Sino-American relations, Stuart still fostered hope for detente or even future cooperation: “Whatever next, I am profoundly grateful to have had a small part in a great half century of Sino-American cultural and spiritual relations, relations which though now apparently broken will, I am confident, be restored as a strong and colorful strand in the emerging pattern of world democracy and international community.”

William B. Pettus, president of the College of Chinese Studies and close friend of Stuart shared his impression about this book in one of his letters during 1954:

I was much pleased to receive from Random House a note saying you had sent me an advance copy of Fifty Years in China. I have since received and read the book with intense interest and am grateful for it. I am much impressed with the wonderful job you have done in making clear the complex problems. I remember seeing a messenger from the State Department hand you a package containing two copies of that terrible White Paper. After I had read this book, I talked with you and others who had served as ambassadors and been much related to China and all expressed disapproval of the book (the White Paper).

Speaking of mixed notices made about Stuart, Chinese Communist Party leader Mao Zedong, in “Farewell, Leighton Stuart!” which was released right after the White Paper, accused Stuart as a China-born American who “deceived quite a number of Chinese,” “hoped to set up shop under a new signboard and to reap some profit” during the Chinese revolution.

In poet Wen Yiduo's last speech in 1946, Stuart was referred to as “an educator and friend of Chinese people.” “He lives in China longer than in the US just like an international student. He understands what Chinese people really ask for,” Wen commented.

Lin Mengxi, a historian and author of Leighton Stuart and Chinese Politics, regarded Stuart as the only American during the 20th century that “took an active part in the political, cultural, and educational spheres of China” and “exerted profound influence.”

The Reinterment Ceremony of John Leighton Stuart (zjol.com.cn)

Stuart died in 1962 in the US. In respect of his final wish, his ashes were transported to China in 2008 and kept at the Anxian Cemetery on the outskirt of Hangzhou where his families were interred. The bilingual inscription on his grave stone reads: “John Leighton Stuart, 1876-1962, first president of Yenching University.”

Written by: Li Wenrui

Edited by: Jacques

Tag: Anniversary 2013