Botany researcher’s lifelong love of reading book helps him unlock secrets of life

Apr 02, 2025

Peking University, April 2, 2025: For Bai Shunong, an emeritus professor from the School of Life Sciences and a Berggruen China Center Fellow, his name has predestined his life trajectory — a deep passion for reading books(“书”) and a research career in botany(“农”).

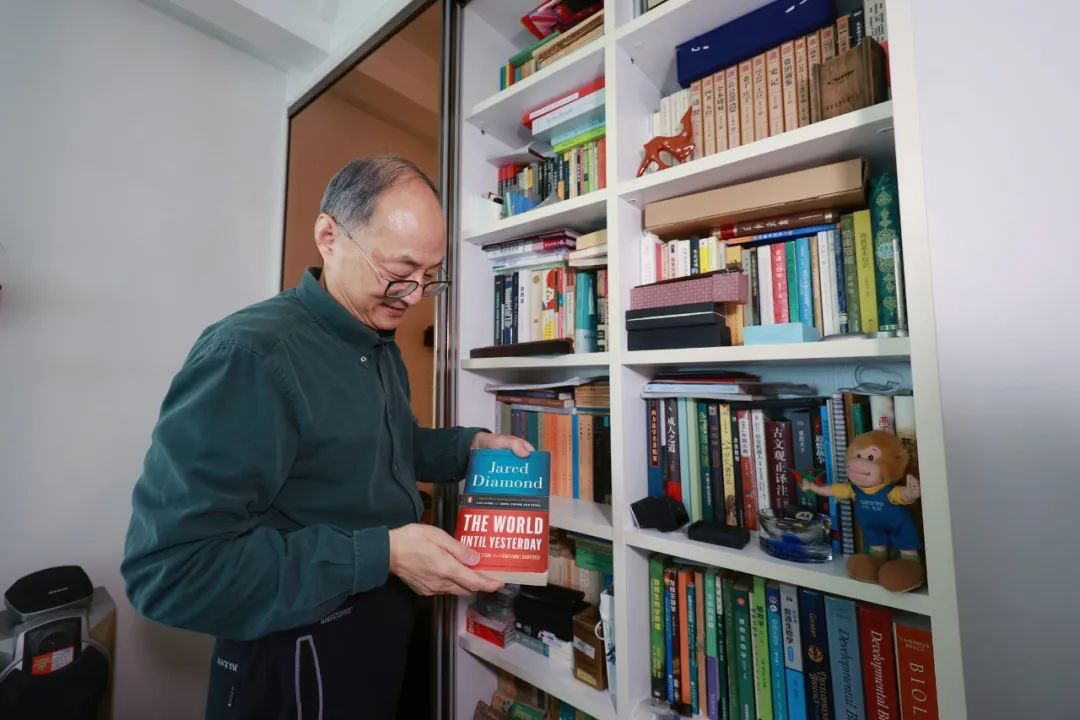

His firm belief in reading as a tool to “shatter intellectual constraints” can be reflected by the numerous bookshelves in his home, neatly filled to capacity with texts on philosophy, biology, linguistics, etc. For Bai, reading is a tool to adopt a “bird’s-eye view” — a top-down perspective critical for evaluating research novelty and feasibility.

While modern academia prioritizes zooming into details, Bai insists on contextualizing the present through classics. “What is ‘forefront’? If you don’t know where we come from, how do you know where we are now?”

In his stash was a seminal book in botany titled Sex in Plant World, published in 1933, which can exemplify this ethos. He traced mainstream logical flaws about defining plant gender using unisexual flowers directly to this book. This gave him a basis to use his own hypothesis about plant outcrossing to resolve these flaws.

“People may think that reading books can widen your horizon. But it’s not like that. You have to think outside the box and adopt a big picture view.”

Bai’s career in botany started out of happenstance, his admission to Anhui Agricultural University largely due to a character in his name which means “agriculture”(农). He became interested in western philosophy during college and read extensively about philosophy and history.

However, a tight research budget limited his foray into books during graduate school, obliging him to focus entirely on the few classical botany textbooks he had. A word-by-word study of the books gave him a systematic understanding of the origin and development of botany, which also elucidated for him meanings of research.

“I have an understanding of historical meanings of botany research, which can be attributed to my experience back then of perusing textbooks.”

After he started working, Bai was constantly pressed for time and seldom had the leisure to read. However, some chance encounters with seasoned scholars at PKU left him impressed with their depth of knowledge, inspiring him to keep reading no matter what.

He credits this habit of voracious reading with helping him overcome setbacks in research. Realizing a stark disparity between realities of research and his perceptions, Bai had decided multiple times to quit his research career, only to be steered back on track time and again by the enlightenment from reading.

As time goes by, Bai has become more selective in books he reads, his choices increasingly driven by specific inquiries he comes across in research and teaching. For instance, his reading now is driven by a quest to distill life into simple principles, which has helped him bridge biology and the humanities, revealing unexpected connections.

“I realized after all these years of botany research that the ultimate motive is actually understand life itself. After you understand life, you can understand people.”

Bai has been imploring students in the humanities to study biology, which he believes can help with understanding human behavior. “However, students and teachers alike in the humanities have a woefully shallow understanding of biology.”

In an instance of bridging biology and human behavior, he rejects the cliché advice to “just be yourself”, arguing that a congregation of humans is actually a gene bank to preserve diversity. He further explains that what makes a species endangered is not its low numbers, but its lack of diversity in gene bank.

Based on this understanding, he concludes that individuals can only obtain resources in society when playing their respective roles, because each person has an allocated task.

“The meaning of life is to find out what role suits you best, and play it to perfection.”

To help more people understand biology, he has taken to teaching science knowledge in simple terms, launching a course and also writing a book, both geared toward general education. Like Darwin’s Origin of Species, his work blurs the line between academia and public discourse.

“I want to use the simplest terms possible to explain what I understand as life, and help people confront the unavoidable fact that people are ‘biological beings’.”

Bai believes that there is a difference between general education and science popularization. The former is a way to a channel a thought process or an opinion through simple language, while the latter is just imparting knowledge.

While acknowledging that both general education and science popularization help carry forward science education in China, Bai stressed that the key lies in using easily understandable language to explain scientific concepts.

In his book, bai has used an assortment of Chinese proverbs and analogies as explanations. For instance, the Central Dogma is compared to a Lego piece assembly line to illustrate the process of protein generation. The proverbs include everyday catch phrases, allusions to Romance of Three Kingdom, etc., making reading fun and educational.

Beside history, Bai also focuses on solving current problems. One relevant topic he contemplates is whether humans need to learn anymore in the age of AI, or learn what?

“There is no correct answer to these questions, but they reveal one fact — advancement of technology will not throttle human’s desire for knowledge.”

According to Bai, humans need to maintain a clear mind in times of fast changes and explore the future while observing the line between human and technology.

Amid today’s dizzying changes, Bai’s relentless pursuit of knowledge keeps him grounded, offering serenity and hope through life’s vicissitudes.

Written by: Yang Yimeng, Liao Kailin

Edited by: Niki Qiu, Chen Shizhuo

Source: PKU Wechat(Chinese)