Peking University, June 10, 2025

Peking University, June 10, 2025: In a discovery that sheds new light on the lives of prehistoric people in China, a team of researchers from Peking University and the Shandong Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology has found genetic evidence of a rare matrilineal community dating back more than 4000 years. Their study, “Ancient DNA reveals a two-clanned matrilineal community in Neolithic China,” was published in Nature.

Why it matters

Why it matters

For more than a century, scholars have theorized that early human societies may have once been organized along maternal lines. Nineteenth-century thinkers like Johann Bachofen and Friedrich Engels argued that matrilineal clans might have been the foundation of early social life, but direct evidence has always been hard to find.

Now, thanks to breakthroughs in ancient DNA technology, this new research provides the first solid genetic proof that such a society really did exist in Neolithic China about 4,750 years ago. The findings challenge long-standing assumptions that ancient societies were predominantly patriarchal. It also gives new insights into how humans once lived and organized themselves.

Key findings

Key findings

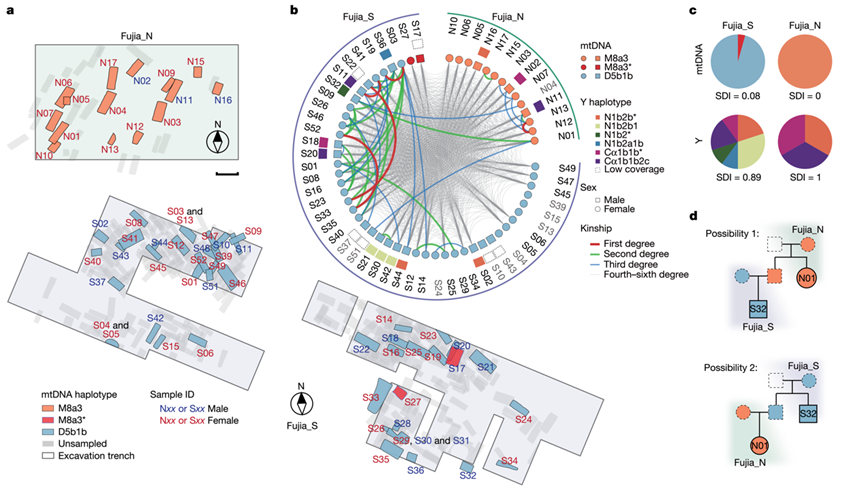

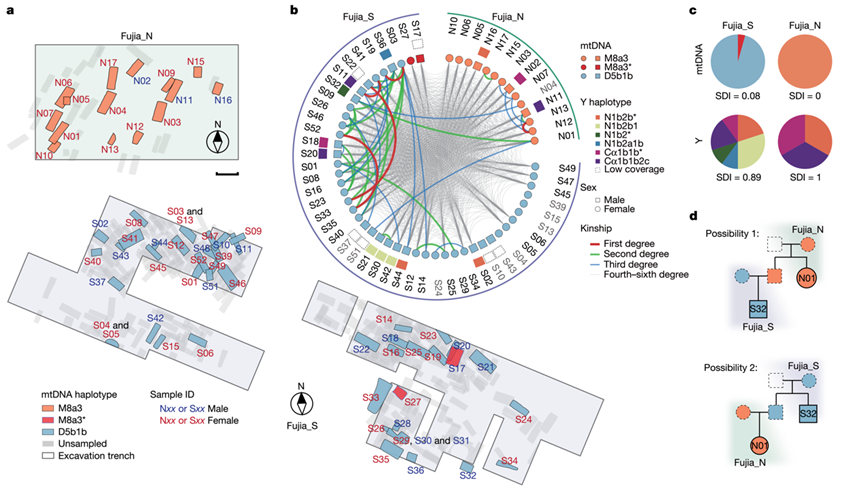

The discovery comes from the Fujia archaeological site in Shandong Province, near the birthplace of Chinese civilization. The site contains two burial grounds from the Dawenkou culture (around 4750–4500 years ago).

Researchers analyzed DNA from the remains of 60 individuals buried there. What they found was striking:

• Everyone buried in the northern cemetery shared the same maternal lineage, as shown by identical mitochondrial DNA (which is passed only through mothers). The same was true in the southern cemetery, where nearly all individuals shared a different maternal lineage.

• In contrast, Y-chromosome data (which tracks paternal lineage) showed great diversity. Men buried at the site came from a wide range of paternal lines. This suggests that while women stayed within their clan for life and were buried with their maternal relatives, men often moved between clans.

This pattern is a hallmark of matrilineal societies, where identity and group membership are determined by the mother’s line, and where strict customs guide burial practices.

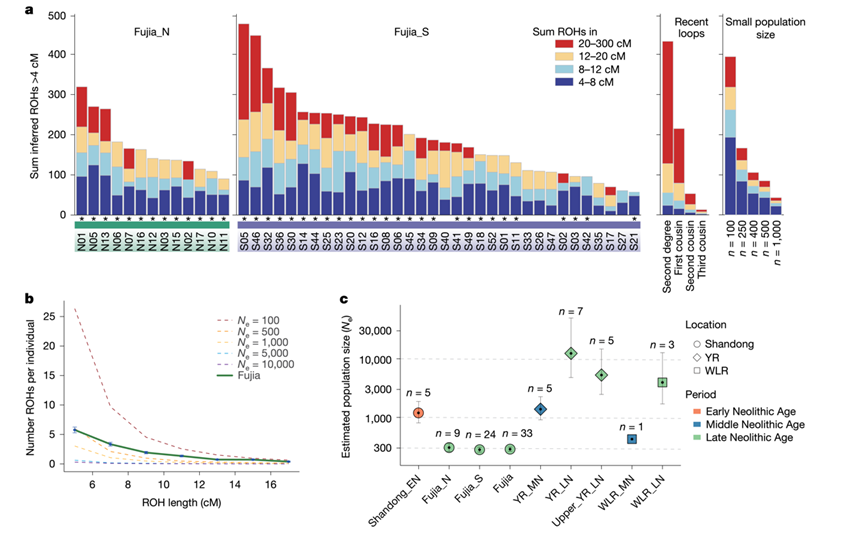

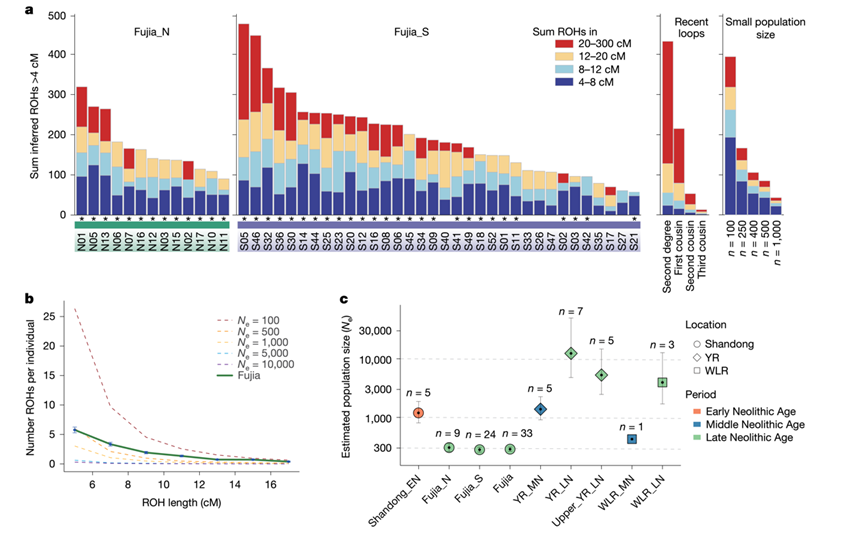

The team also examined diet and mobility by analyzing isotopes in the bones and teeth of those buried at the site. They found that:

• The community lived a highly localized life in a narrow stretch of coastal land near the Yellow River delta. Their diet centered on millet, with some marine foods likely supplementing their meals.

• There was little sign of social inequality because grave goods were modest, craft production was basic, and trade links were limited.

In other words, this was a relatively simple, egalitarian farming community organized around two matrilineal clans, with little wealth accumulation or rigid hierarchy.

Implications

Until now, no such society from this early period had been directly confirmed through genetic evidence anywhere in East Asia. The findings from Fujia offer a glimpse into a time when mothers and their lineages formed the core of community life. It was a social structure that would later give way to the patriarchal systems that dominate much of recorded history.

The study also highlights the enormous potential of combining ancient DNA analysis with traditional archaeology. By doing so, researchers can reconstruct not only how ancient people looked or what they ate, but also how they related to one another and built their societies.

This article is featured in the "Why It Matters" series. More from this series

Read more: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41586-025-09103-x

Written by: Sean Tan

Edited by: Chen Shizhuo