Peking University, May 22, 2011: In order to stabilize prices, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC), China's chief economic policy-making body, has "interviewed" (yuetan) several companies in different fields, such as instant noodles, daily health products, and wine to ask them to postpone raising prices. Professor Deng Feng from the Law School of Peking University (PKU) analyzed this phenomenon.

Professor Deng Feng

Recently, inflation has turned from a tip of scholars to a current focus. Pressure from the public has led to a series of chain reactions. In economic policy, the problem of expanding the domestic demand, which always needs to be addressed, has turned from stimulating private consumption by public consumption to preventing the decrease in private consumption because of rise in price.

Stabilizing prices has become a top priority. It is directly linked to people’s livelihood and even their support for the government. The NDRC and industry associations persisting in self-discipline prices seek vacancies in law and create new words for public administration and morality, expanding the boundary of public administration after expansionary fiscal and monetary policies.

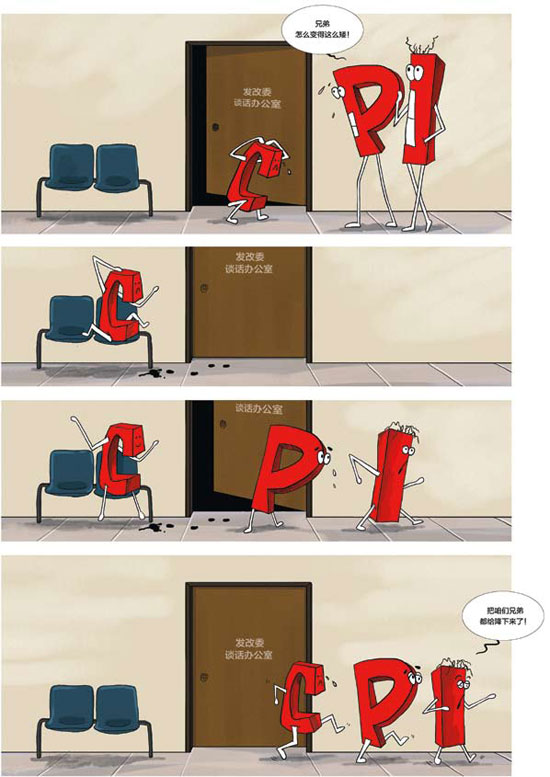

"All lowered!": before and after an NDRC "interview" (Caing.com)

"Righteous" Regulation

The NDRC has taken all to control prices, from beforehand preventive interview to afterwards punishments. Unlike the quiet approval of price hike in infrastructure and public products, the NDRC has taken a justified attitude this time.

In motivation, stabilizing prices has a correct political motivation, whether from the above or from the below. In theory, experts from the NDRC attribute reasons of this problem to the market failure and its limitations. In purpose, the NDRC claims that its aim is to guide enterprises to exercise its decision-making right of prices rather than administrative intervention or interference in the decision-making power of enterprises. In opportunity, it is intervention in advance to prevent violations. In the distribution of duties, it is the social responsibility of enterprises. While in effect, it is overall good.

Interview and punishment has become two NDRC weapons to control prices. Especially the former, from industry association to specific enterprises, all can be interviewed without exceptions. According to official explanation, interview doesn’t belong to intervention, the limit to decision-making power of the counterpart, or formal administrative procedure. Instead, it is genial, flexible, and preventive enforcement, or even institutional innovation, which can be categorized into “soft law” proposed by administrative scholars. However, punishment is a resolute and accurate legal means on just grounds with a legal basis.

Many public opinions have appeared regarding to NDRC's determination, behavior, and strategy. People have such doubts as whether the interview is an administrative intervention, the interview leads to direct control effect or delaying effect, whether interview objects should be expanded to the central bank issuing currency and regarded as the source of the inflation, whether the interview content should be expanded from the prevention of price hike to the prevention of decrease in quantity or quality, and whether the interview field should be expanded from the commodity and food industry to the real estate industry which earns a much larger profit.

"Authority-excessing" Intervention

There is no doubt that the NDRC needs not only a strong logic to persuade enterprises and industry associations, but also a strong mental quality and logic to persuade itself.

From a perspective of a scholar in law, regulation like interview and punishment is not a problem of conceptual definition or labeling, a problem of proper motivation, or a problem of right distribution.

Maybe the explanation of market limitations is in line with the mainstream opinion of economics. Maybe the position of interview and punishment conforms to the basic framework of the Administrative Law paying attention to administrative procedure control and administrative rights exercise. However, the NDRC’s price regulations don’t accord with legal rules and due logic regulating public economy and the market.

It’s a bad choice for the NDRC to make explanations that interview means no administrative intervention, which is not necessarily wrong even in the opinion of the mainstream economics. Because the government has various public distribution targets such as controlling strategic industry, supporting small and medium enterprises, providing social security, and helping vulnerable groups.

The reason why administrative intervention becomes a derogatory term may come from the ideology and public opinion in which market, competition, freedom, and individual rights have become commendatory terms. Maybe it is also from more canonical constitutional control procedure which administrative intervention needs and even from public fear for the abuse of power by government administrations.

Then a paradox appears: the attitude and actions of the NDRC dealing with price hikes come from the distribution target or the market target?

If out of the distribution target, the NDRC is right in sense of justice but exceeds the power authorized by law in action. Besides, the distribution target usually needs a political process and authorization procedure. Therefore, interview should at first be authorized.

If out of the market target, the NDRC’s behavior should follow two basic principles: appropriate authorization and professional unity of targets, means, and responsibilities in accord with law. According to the 1st, 26th, 27th, 31st and 32nd articles of the Price Law, the NDRC is not entitled to intervene prices out of the distribution target.

The 3rd and 5th article of the Price Law clearly establish the division of public and private products in line with theories. The areas of the NDRC responsible for prices are mainly government guiding prices and government pricing.

It’s obvious that the interview object exceeds the authorization by the Price Law to the NDRC, not to mention the nature of interview. Therefore, interview means intervention.

"Unilateral" Accountability

The NDRC gave an ambiguous explanation of its understanding to the Price Law: although not responsible for the level of market prices, the NDRC is responsible for the supervision of market pricing behavior. The 2nd chapter of the Price Law stipulates many inappropriate pricing behaviors of businessmen, which the NDRC intervenes in advance to prevent.

There is usually a close relationship between pricing behavior and price level. Using punishment for pricing behavior to control prices may be one of the most technological reasons given by the NDRC, which is applied to the punishment for Unilever.

However, the understanding of enforcement in this way needs further consideration. The first is the understanding of the Price Law and the nature of enforcement dealing with market pricing behavior. If this kind of understanding aims at the price level, it belongs to a regulation based on public goals. If it aims at the pricing behavior, it falls into the category of the Law Against Unfair Competition.

Competition should follow the market logic. The NDRC took little consideration to “reasonable commercial purposes” or “competition logic”. It was just on moral grounds like “fake”, “bidding up”, or “sudden huge profits” in its enforcement cases. It’s obvious that no price hike is inappropriate commercial purposes in inflation as no one will guarantee the interests of investor and workers without price hike.

The second is the misunderstanding of enforcement. Enforcement should follow the principle of due process, follow the principle of presumption of innocence, especially in the case where the law stipulates the pricing power of businessmen. The NDRC should follow the basic principles and enforcement process.

What’s more, the NDRC imposed moral obligations like social responsibility onto enterprises. But there’s a complicated relationship between no price hike and social responsibility. No price hike may lead to loss, which means irresponsibility for stakeholders. Enterprises may have more ability to take social responsibility after price hike.

There is another word for social responsibility–“accountability”, which means the due responsibility taken by all relating to public affairs. The government should stand out first and foremost.

“Accountability” sometimes means the relevant people should be blamed when something goes wrong. The Price Law stipulates accountability for businessmen and law-executors but not law enforcement agencies. In other words, maybe the essence of the problem is that regulated objects can take no effective measures to cope with “prevention enforcement” enacted by the NDRC to control prices under existing legal mechanism.

What can be concluded is that the NDRC itself does not believe in its ability to control prices, either. Taking intolerable anger as a proper motivation, the unjustified means just shows its incompetence.

The Price Law

Article 1 This law is formulated with a view to standardizing price behavior so as to strengthen their role in rational disposition of resources, stabilize the general price level of the market, protect the lawful rights and interests of consumers and business operators and then promote the healthy development of the socialist market economy.

Article 3 The State shall introduce and gradually improve the mechanism of regulation of prices mainly through market force and under a kind of macroeconomic control. Under such a mechanism, pricing should be made to accord with the value law with most of the merchandises and services to adopt market regulated prices while only a few of them to be put under government-set or guided prices.

Market-regulated prices refer to prices fixed independently by business operators through market competition. "Business operator" used in this law refers to legal persons, other organizations or individuals that engage in production or marketing of merchandises or provide paid services.

Government-guided prices refer to prices as fixed by business operators according to benchmark prices and range of the prices as set by the government department in charge of price or other related departments within their term of reference.

Government-set prices as fixed by the government department in charge of prices or related departments within their term of reference according to the provisions of this law.

Article 5 The State Council department in charge of prices shall be responsible for the administration of the work related to prices in the whole country and other related departments shall be responsible for such work within their terms of reference.

Price departments of the people’s governments at and above the county level shall be responsible for the work related to prices within the regions under their jurisdiction. Price departments of the people’s governments at and above the county level shall be responsible for the work related to prices within their terms of reference.

Article 26 To stabilize the general price level is one of the major objectives of macro-economic policy. The State shall set targets for the monitoring and adjustment of general price level in the light of the requirements of the development of the national economy and the endurance of the people, list them into the national economic and social development programs and help their realization through means of monetary, fiscal, investment and import and export policies and measures.

Article 27 The government shall build a major merchandise reserve system and establish a price regulation fund to control prices and stabilize the market.

Article 31 When such abnormalities as violent fluctuation in the general price level occur nationwide, the State Council shall introduce power for the concentrated fixation of prices in the whole country or part of the regions for the time being or adopt such emergency measures as freezing part or all prices.

Article 32 The intervention or emergency measures introduced according to the provisions of Article 30 and Article 31 shall be removed or lifted in time when the situations that call for such measures disappear.

Background Info:

Deng Feng is an associate professor of PKU Law School. He was born in Shandong Province in 1973. He got his Bachelor of Law (1995), Master of Law (1998), and Doctor of Law (2001) from Law School of Renmin University of China in succession, majored in the Economic Law. He studied at the PKU Guanghua School of Management as a post-doctoral majored in Industrial Organization Theory from 2001 to 2003. After that, he joined the faculty of PKU Law School. He visited Harvard University as a Harvard-Yenching fellow from 2006 to 2007, focusing on the historical law and economics. Now, he serves as co-director of Institute of Law and Economics, PKU.

Deng's study interest lies in corporation and enterprise law, regulation and antitrust, and law and economics. He taught classes include Corporation and Enterprise law (autumn), General Principles of Economic Law (spring), Corporate Governance and Firm Theory (spring), Law and Economics (spring), Merger, Acquisition & Reorganization (autumn), and Practical Contracting (spring) both for undergraduated and postgrauduated students. He published several books, including Common Corporation Law, Pandect of Economic Law (co-author), and over 50 articles, essays, and papers.

Written by: Zhang Hao

Edited by: Su Juan

Source: Caing.com